Maria, Alexandra, Constantine...

diving into the archives and getting to know my ancestors

At the end of last year I took a memoir writing class. I wasn’t - and still am not - planning on writing a memoir, but I wanted to (a) get back to more creative writing which I loved when I was younger (and which I abandoned out of fear of sharing my work with anyone) and (b) to write more for my Arts Council funded project Everything Was Forever (Until It Ended) which deals with intergenerational trauma and collective memory through the lens of my own family’s history. As I’m slowly continuing to untangle the various story threads and trying to connect them into a semblance of a narrative, I figured I can share some of the writing I did for the project (which may or may not end up in the final version of it).

Maria, Alexandra, Alexandra, Petr, Pavel, Alexander, Constantine, Constantine… Page after page of names written in neat script handwriting, with some of the letters that no longer exist in the Russian alphabet.

Vera, Olga, Anna, Zinaida, Michael, Michael, Olga, Ioan. Some are very old orthodox names, rarely in use today, others faired much better in the course of history. They come in clusters - Antoninas in February and March, Veras around September time. Back then, children were often named after the saints honoured around their date of birth, and in Russian Orthodox tradition those name days were usually celebrated much more than the children’s birthdays.

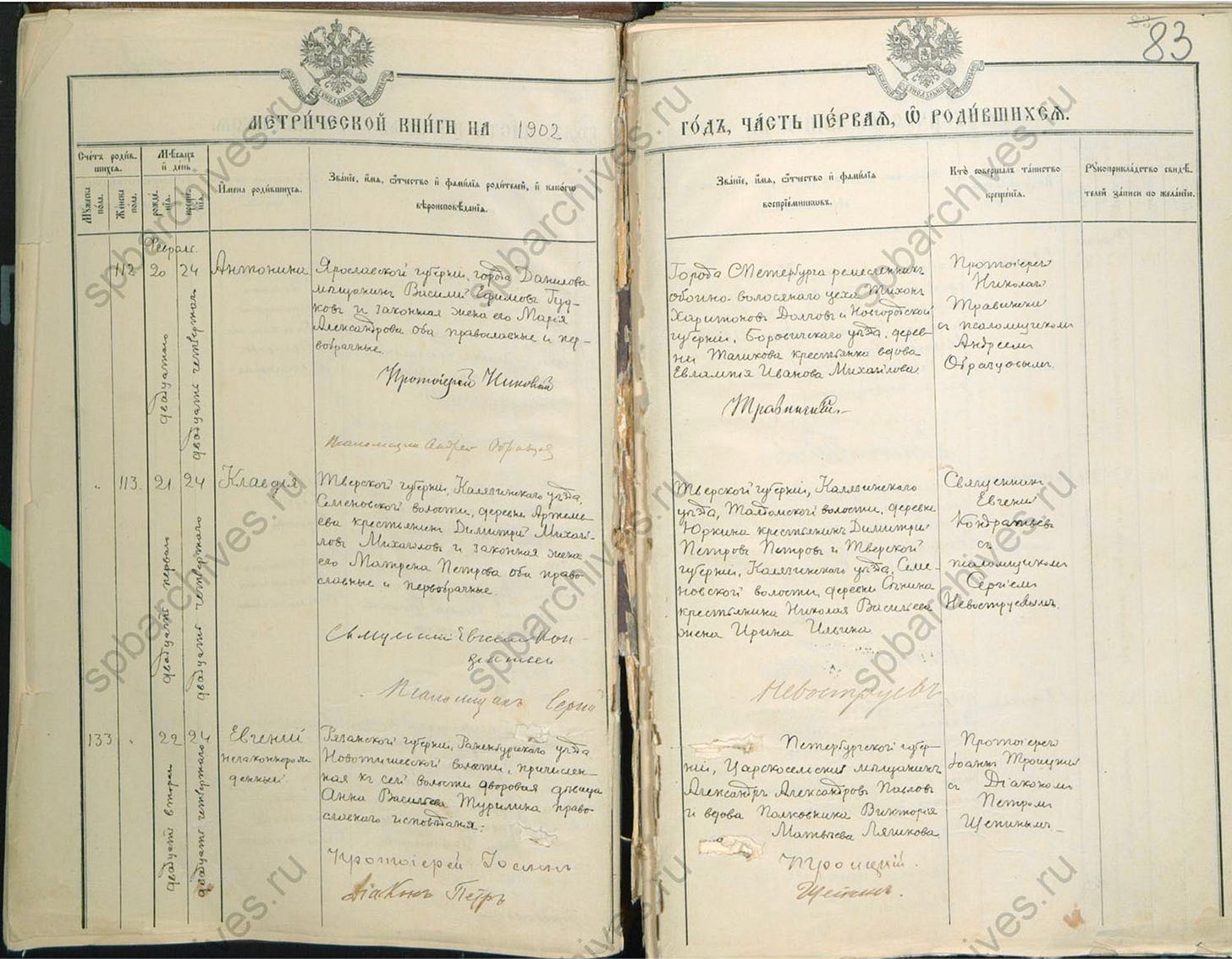

I’m looking through the so-called “metric books” - pre-1917 church records of births, weddings and deaths compiled by each local parish.

I note how many of those names have “illegitimate” neatly written under them, a brand you carried with you all your life, part of your identity. I get strangely excited when I spot twins: there were no twins in my family but they’d always fascinated me. I had twin friends when I was growing up, the only person outside their family to tell them apart, but that is the extent of my experience with multiples.

A few weeks ago I met - over Zoom - with an archivist named Maria. On top of her day job she helps people trace their roots using historical archival documents. She explains what’s available, how to search (and where) but insists that the best way to do it is not to commission her, but to do it myself, to feel the rush of discovery, to hold the documents in my hands. She is right.

It took me a while to get the hang of the online archives. I thought I’d lose the will to live waiting for each individual query to load, being randomly logged off without warning, not finding anything of value. Not knowing where to look really.

But then, late at night, I had a breakthrough. Finding old parish maps, I’d listed possible churches my great-great-grandparents could have belonged to. A task not for the faint of heart, as maps have been redrawn several times since - but I love releasing my inner Sherlock Holmes. The first church I tried didn’t lead to anything, but with the next one I struck gold.

The Dormition of the Holy Mother of God was a late 18th century cathedral in the baroque style that was blown up in the 1960s in another bout of anti-religion campaigning, making way for an underground station rather ironically named “The Peace Square”. At the turn of the 20th century it was one of the most important cathedrals - and one of the richest parishes - in St Petersburg, and was located just down the road from the still surviving house were my great-great-grandfather lived and worked before the revolution of 1917 changed everything.

I know almost nothing about Vasily Goodkov, and I’m hoping that through the records of births of his six children - including my great-grandmother Antonina, who I am named after - I will glean more information about his life and where he came from... where I came from.

With St.Petersburg, the former capital of the Russian Empire, being founded only in 1703, built on a boggy marsh and on the bones of the peasants brought in to tame the nature here, no one living in the city today can truly claim to be it’s native. Everyone’s ancestors moved there in the 18th and 19th centuries in search of opportunity and wealth. And they got it, for a time - until the “city of three revolutions” upended their lives in ways no one could have imagined or predicted.

Vera, Olga, Anna, Michael, Michael, Olga, Serhiy, Pavel, Antonina…

Finding my great-grandmother was easy. I knew her birth year - 1902 - and a month - February, so I locate her birth record fairly quickly. Her date of birth is off by a couple of days from the Soviet-issued birth certificate but I’m not really surprised - her own daughter’s birth was only registered a year later, apparently a common practice in those days.

What’s more important is that next to her birth and baptism dates, I have a record of her parents. Vasily and Maria, “both of orthodox religion and of the first marriage” the book says.

As expected, the focus of all the children’s birth records - bar the “illegitimate” ones - is on the father of the child. I get my first real glimpse of his story. He’s described as a “tradesman of the city of Danilov of Yaroslavsakya Province” and now I know where he came from. Danilov is over 400 miles away from St. Petersburg, and it’s likely would have taken him a couple of weeks by horse and wagon to reach his destination. Moscow, although - temporarily - not a capital - would have been a lot closer, but he landed in St. Petersburg - I wonder why?

A tradesman, a meshchanin - now a rather derogatory Russian word denoting a person with limited interests and education - was a social class a rank just below a wealthy merchant. This social class was hereditary - the only way to move up on the social ladder was either to get an education and move into state service, or to buy your way up to a merchant guild which not everyone could afford to do.

Exhale. I now know for a fact I’ve found the right church, and assuming the family haven’t moved before they were forced to by the Bolsheviks, I will keep looking here.

Next, I have a list of my great-grandmother’s five siblings, with some of their years if not exact dates of birth. Most of them have perished during the Second World war, dying of starvation in the besieged Leningrad - and they were never really talked about in our family. In an inspired move, about 20 years ago, I sat down with my grandmother and got her to tell me all she could still remember about her aunts and uncles, and point them out on old family photographs. That’s the only reason I have that list - as vague as it is - at all.

I get lucky early on with the youngest, Anatoly, born in April 1912. It’s an exciting discovery - he was real, after all. I had my doubts. Finding Anatoly also means that for the 10 years between Antonina’s birth and his, their parents stayed put. So, I keep going.

It takes me the whole day. I forget to have lunch, munching on pot-noodles without taking my eyes off the screen, and letting my son play computer games all day in his pyjamas. I’m obsessed. All the others siblings’ years of birth that I thought I knew turned out to be way off. I trawl through all the records, from 1892 until 1912, 500 pages each, in search of names, hoping that I at least have the correct ones - you just never know with my family.

Maria, Alexandra, Alexandra, Petr, Pavel, Alexander, Constantine, Constantine…

It’s almost trance-like. I click and click and click, from one scanned page to the next, making myself read names out loud so I don’t accidentally skip any. Each correct name I find - Olga, Nadezhda, Constantine, Nikanor - I stop and check the parents. It’s easy now I know which province and social class to look out for, so I can scan the records quicker.

Two days in, I’ve found all but one, Nikanor. The eldest of 6, he must have been born elsewhere - or he’s even older than we thought. I’ll keep looking, but not right now. I’m exhausted.

I look at my finding so far. Scraps of paper, with years crossed out, question marks and notes of “births not found”.

1897. Constantine.

1902. Antonina.

1904. Olga.

1909. Nadezhda.

1912. Anatoly.

There are large gaps between Constantine and Antonina, and Olga and Nadezhda. They must have had more children we don’t know about. My mother - following my progress on WhatsApp - is sceptical. “Oh, they’d been getting on in years you know, they probably didn’t have any more. Grandmother never told me about any other siblings”.

But I have a hunch. Her grandmother might have not known. A distinct possibility given everything I know about my ancestors so far - our family just doesn’t like to share.

This time, instead of looking at births, I’m looking at deaths. It’s harder going, there isn’t a clear list of names to scan through. Each death is recorded with a neatly written paragraph, describing the deceased’s social status and area of birth, and in case of children starting from the father’s social class and location of birth, only then followed by the name of the child. It’s slower to begin with but I quickly find my rhythm.

Peasant, Peasant, Peasant… I can dismiss those. Vasily was a tradesman, so his record will start with that - or the name of the province he comes from.

I keep going. Just looking through these records is an education. I’m learning more about the make up of the pre-revolution St Petersburg than I’ve ever learned at school. The provinces people migrated from, their social classes, ages and causes their deaths (from “self-hanging due to a bout of mental illness” to “diarrhoea” to “natural weakness”), peasants (a vast majority) recorded next to statesmen and noblemen, it’s all here, it gives me a picture of life as it was then better than any history book ever could.

And then… Here it is. Tradesman’s Vasily Goodkov’s son, Pavel, passing away aged 6 months and 10 days, cause of death: weakness.

I should be sad for the loss of a young child, but I’m actually excited. I feel a bit like Howard Carter stepping into the Tutankhamen’s tomb for the first time. I message mum, and she calls back immediately. “Pavel is an unlucky name for our family. Grandmother’s first child was also named Pavel, and he passed away only 2 days old”.

My hunch was correct - they did have other children - well at least one. Now I flip back to the beginning of the same metric book, and search for Pavel’s birth.

After a few short minutes I find it. 31st of May 1900. Pavel and Peter. The names of two guardians saints of the city of St Petersburg. Two boys.

There were twins in my family after all!

* * *

The family had lost their second twin a just few months later. Peter’s death entry is brief, giving a minimal amount of information on the father, in contrast to other records. The words on the page themselves looks bereft, somehow. Cause of death: “inflammation of the brain”. I think that multiples were a definite death sentence back then.

Ten months after the passing of the second twin, my great-grandmother Antonina was born. All her mother’s grief of losing two children in quick succession, passed onto her, too.

That’s amazing work, Antonina, well done! I would love to do the same, specially if it’s online. Is there a link or email that you could share? Thanks!

Oh this is fascinating! I am obsessed with researching my tree too and so totally get it, you can get so lost in it!